WaPo reports Activist Aims to Scare Officials Into Protecting Personal Data

WaPo reports Activist Aims to Scare Officials Into Protecting Personal Data

Betty (but call her BJ) Ostergren, a feisty 56-year-old from just north of Richmond, is driven to make important people angry. She puts their Social Security numbers on her Web site, or links to where they can be found. It's not that she wants CIA Director Porter J. Goss, former secretary of state Colin L. Powell, or Florida Gov. Jeb Bush to be victims of identity theft, as were millions of Americans in the past year. Ostergren is on a crusade to scare and shame public officials into doing something about how easy it is to get sensitive personal data. Data brokers such as ChoicePoint Inc. and LexisNexis Group have been attractive targets for identity thieves because they are giant buyers and sellers of personal data on millions of people.

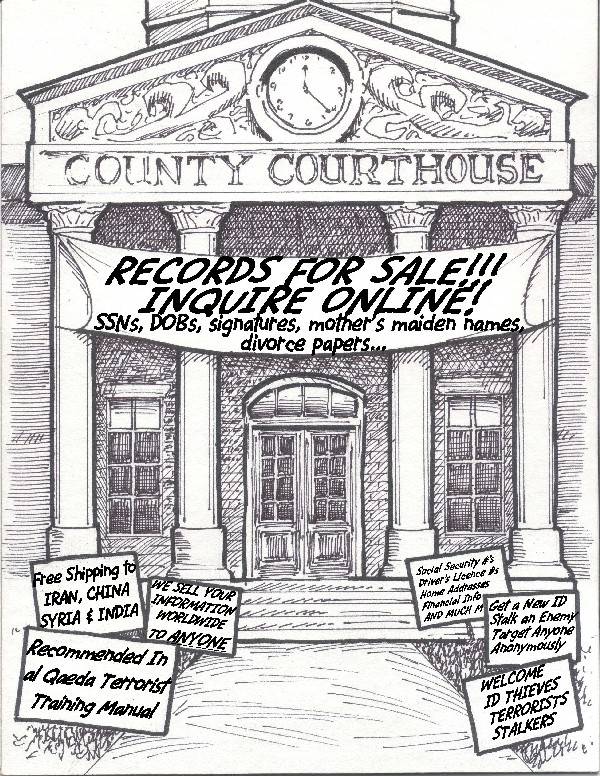

But as federal and state lawmakers try to keep sensitive information from falling into criminal hands, they face a difficult dilemma: The information typically originates from records gathered and stored by public agencies, available for anyone to see in courthouses and government buildings around the country. What's more, local governments have in recent years rushed to put these records online. A wealth of documents -- including marriage and divorce records, property deeds, and military discharge papers -- containing Social Security numbers, dates of birth and other sensitive information is accessible from any computer anywhere. Many of the online records are images of original documents, which also display people's signatures.

I applaud the local governments making public data available online, but they should non show things like Social Security numbers or signatures. This even points out how bad it is that Social Security numbers are used for identification, yet the social security card is so easy to forge. We need to have ID cards that are impossible to forge, and which use several forms of biometric data, and those numbers could be used for identification numbers.Ostergren began organizing citizens and complaining to officials on the issue in 2002, when a title examiner called to warn her that her county was about to put a slew of documents online, including pages with her signature. A longtime activist in local politics, Ostergren swung into action, bringing enough pressure on Hanover County officials that they halted their plans. Then she broadened her attack, targeting other counties in Virginia and elsewhere. Today, she is eager to guide reporters to her favorite example: the Social Security number of House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-Tex.), which is viewable via the Internet on a tax lien filed against him in 1980. "Don't you think if I can get Tom DeLay's Social Security number . . . that some guy in an Internet cafe in Pakistan can, too?" she asks, her voice rising with indignation. "It's just ridiculous what we're doing in this country."

She makes a very valid pointThe drumbeat of identity-theft revelations is the stuff of nightmares for cash-strapped county recorders, court clerks and other custodians of public records, even without people like Ostergren hounding them. They could start masking out sensitive data tomorrow for new documents they receive, but billions of records already are online. "It's a national issue and it's hitting everybody," said Kathi L. Guay, the register of deeds in Merrimack County, N.H., who participates on a joint task force of public agencies and companies addressing the issue. In addition to providing citizens with information on how their government operates, many public records are essential for commerce.

Knowing who has legal title to property, for example, is necessary for real estate transactions. The presence of a tax lien can also affect a person's ability to buy or sell property or other goods. In some circumstances, Social Security numbers can help distinguish between people with common names. But for decades, Social Security numbers, mothers' maiden names and other crucial forms of personal identity were routinely included in dozens of documents, regardless of whether they were essential and with little thought to the consequences. That, in turn, enabled companies such as ChoicePoint to send workers to courthouses across the country to scoop up the data for their databanks. The information is collated, or analyzed, and sold to other companies and back to government agencies. Many counties package their data to make it easier for database companies to collect it.

And easy for identity th"Public records laws were designed to shed the light on government activities, not our personal information," said Kerry Smith, an attorney with Public Interest Research Groups, a coalition of state consumer advocacy organizations. States are "clearly not striking the right balance when they release our Social Security numbers -- the key to our financial identity -- to commercial data brokers and anyone with access to the Internet." Some states have passed or are considering laws restricting the release of certain kinds of data. Florida, for instance, gives consumers the right to have Social Security numbers and other data blacked out from view online. But few local governments have the resources to go into all existing online records to remove sensitive data. "Usually when you are talking about these issues, no one is talking about it retroactively," said Chris Jay Hoofnagle, West Coast director of the Electronic Information Privacy Center, an advocacy group. "They are talking as if it can't be addressed. Which is too bad."

One exception is Orange County, Fla., which recently awarded a $500,000 contract to a private company that will comb through its 26 million pages of online records, masking Social Security numbers and other confidential information. "The mortgage lenders and title searchers are very concerned that we are hiding things," said Carol Foglesong, the assistant county comptroller. "But my answer is, 'I sure don't want to take the whole document away.' " The Florida Legislature has ordered the masking of data to be completed throughout the state by the beginning of 2006, but so far only eight counties have signed contracts for the work, said Foglesong, who expects an extension. Foglesong and others are pinning their hopes on technology.

Companies that mine data often boast that they can use software to collect individual pieces of data from images of documents that are posted online. Similar technology can be used to mask certain data. But many in the industry are pessimistic that nationally, sufficient resources will be available. "It's probably going to be a county-by-county undertaking, as record custodians are able to convince local administrators that this is worthy of taxpayer dollars," said Mark Ladd, a former register of deeds in Wisconsin who works on privacy issues for the Property Records Industry Association. Ostergren sees the solution in more simple terms: Keep public records public, but don't put them online. "If you want to go snooping in my records, you drive to the courthouse," Ostergren said. Most identity thieves, she reasons, will neither take the time nor want to be seen. In the meantime, she pursues her guerrilla campaign. Her formula is simple: Target a county, locate personal data on hundreds of residents, send them letters telling them how much of their personal information is or might be exposed online, and urge them to pressure their local officials. "I thought it was the most ludicrous thing I had ever heard of," said Mary Guest, recalling her reaction when she got a letter from Ostergren while living in Front Royal a couple of years ago. When she found out it was true, Guest -- whose husband had been in the Virginia House of Delegates before he died -- began pressing Warren County officials not to post records online, which they so far have not done. When Ostergren finds a well-known figure, she decides whether exposing his or her number on her Virginia Watchdog Web site might further her cause.

Which is how she came to link to Jeb Bush's Social Security number. She notified him through someone she knew in the administration of President Bush. Soon after, she noticed that the governor's number was blacked out on the county Web site in Florida where it was listed. So she posted it on her site. "I decided since he protected his own hind end and nobody else's, I'd put his on there," she said.

James Joyner blogged A Richmond, Virginia woman is posting the Social Security Number and other sensitive information on some major public officials on her website, in order to spur action on the issue of identity theft. I applaud Ostergren's enthusiasm on this issue--my girlfriend's identity has been stolen twice and there seems little interest in doing much about it on the part of creditors--but agree with Cori Dauber that this methodology is extreme. What's more, it's rather silly. What exactly are Goss and Powell supposed to do about identity theft? Powell is no longer in public office and Goss is out of the legislature.

Cori Dauber blogged Clearly we have a problem with personal data being far too available to bad actors. It's wonderful to hear that individual activists are making a point of pushing the issue to the forefront of debate (although I don't know what to make of the proposals being discussed in the article, since alternatives are not cross-compared.) But is it really necessary to get attention by posting the personal information of prominent political leaders? And did the Post help matters by making it so easy to find this woman's site?

That is true. I found it easily with Google using her name.(By the way, the blurb on the Post's home page refers to "activists." But I only see mention of one woman who's actually engaged in this behavior.)

Vox Day blogged I'm all for this. If they're going to cram it down the throats of the American people, the American people should make sure that they get to experience the full consequences of their evil, idiotic actions.

No comments:

Post a Comment